Case Studies: Migration, refugees, racism and discrimination

#LetThemStay #BringThemHere

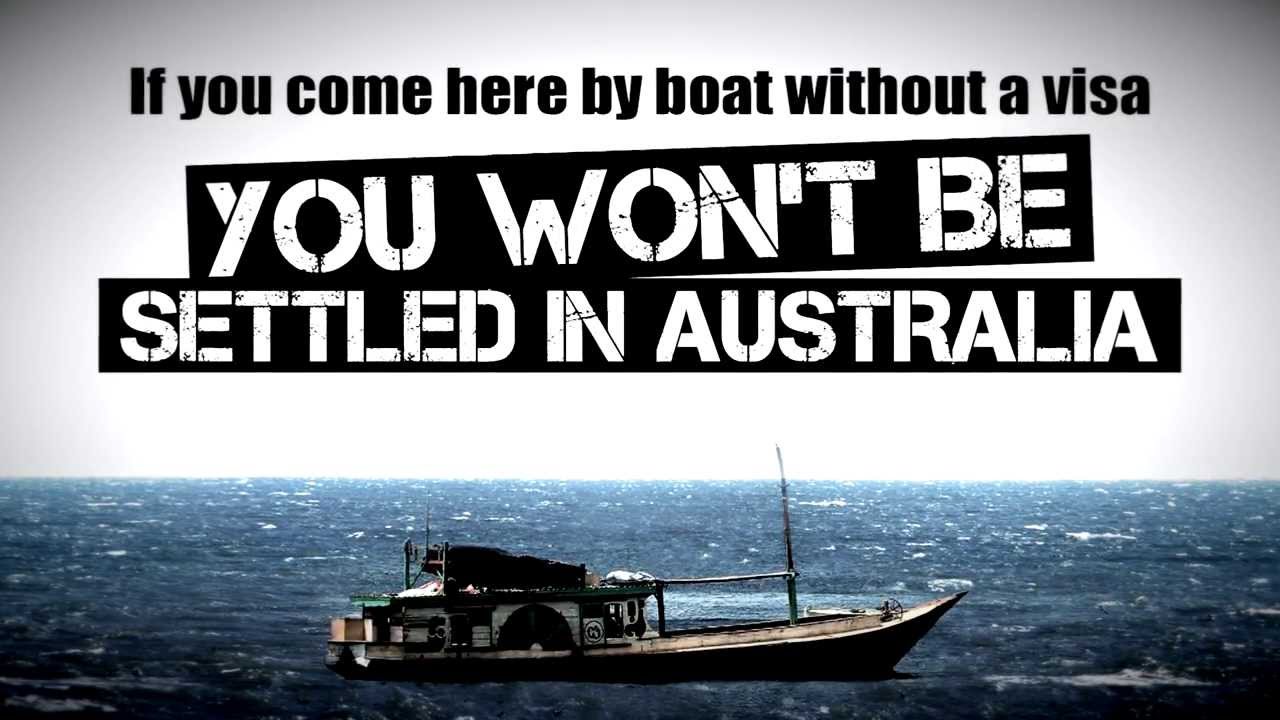

The story: over a number of years, Australians joined together in protest against a humanitarian crisis and inhuman conditions against refugees detained in offshore detention centres, where vessels carrying asylum seekers predominantly from Afghanistan, Iran and Sri Lanka continue to be intercepted and sent to detention centres created on Nauru and Manus Island, Papau New Guinea. Many Australians want refugees being detained in these offshore detention centres to be resettled and safe, which have been in use over many years (Manus has been in use since 2012).

In February 2016 a 12-month old baby was transferred from Nauru to Brisbane for medical reasons, was due to be transferred back to Nauru when doctors in the hospital refused to discharge her due to the detention facilities not being safe. A spokesperson for the hospital confirmed: ‘As is the case with every child who presents at the hospital, this patient will only be discharged once a suitable home environment is identified.’

Outside Peter Dutton's Brisbane office now! #LetThemStay #Brisbane #CloseTheCamps #Manus #Nauru #BringThemHere pic.twitter.com/yo3wsyg9l2

— HelpRefugeesOZ ✊🏼#FreedomForAll (@HelpRefugeesOZ) February 12, 2016

Baby Asha was classified as an “illegal maritime arrival”, despite being born in Australia, because of the immigration status of her parents. Her story galvanised communities across Australia in the #LetThemStay movement and wider sanctuary movement, where social media was used to organise a vigil and a blockade of the hospital by supporters to prevent the Immigration Department from entering/exiting with the child. The government backed down and agreed to a temporary stay in Australia.

Since the Nauru Files investigation by The Guardian into 2,000 incident reports from the Australian-run immigration detention centre in August 2016, snap protests against the government’s policy concerning asylum seekers have spread across the country, particularly in November 2016. Hashtag frenzies that were once driven by fear and insecurity, such as #stoptheboats and #wearefull, have over the last five years changed to ones bound in unity and compassion such as #bringthemhere and #letthemstay.

Sydney You know the government has failed when Grandmas start to riot (-: #CloseTheCamps #BringThemHere pic.twitter.com/y2W2Lt17ma

— Catherine (@catherinemaths) August 27, 2016

Aussie schools are walking out with you #NationalSchoolWalkout #NeverAgain #NationalWalkoutDay #NationalStudentWalkout #eraforchange pic.twitter.com/QPL7PVz5oh

— ERA for Change (@ERAforChange) March 15, 2018

The campaigns used hashtags to promote public awareness of the issue, allowing journalists, politicians and protesters alike to voice their critique of the government’s asylum seeking and refugee policies. In addition, they can spread information such as the time and location of rallies, gaining traction to put pressure on politicians and political leaders that their responsibilities to the refugee convention and to the human rights of others cannot be simply subcontracted to other countries out-of-sight and out-of-mind in Australia.

The who: GetUp, Edmund Rice Centre for Justice and Community Education, Refugee Action Collective, Edmund Rice schools network, Amnesty International Australia (and more!)

The issues: Asylum seeking, refugee convention, compassion

The medium: Twitter, Facebook and YouTube, GetUp

The time-frame: 2011 – ongoing

The impact: Changing the language of public discussions on being ‘tough on border protection’ has been a driving force of campaign energy, both online and offline. Many groups and individuals participate openly, with increasing creativity and decentralised actions such as protestors hanging signs on the Opera House and interruptions at the Melbourne Cup (Australia’s biggest annual horse race) in 2017, the post primary schools national solidarity protests Detention for Detention and bumper stickers such as the Edmund Rice Centre’s ‘Make Compassion Great Again’ bumper sticker.

Other actions include crowdsourcing funding to get pre-made ads placed on TV and radio that tells the true story of one family forced apart by offshore detention, to convince Australians that they should #BringThemHere; crowdsourcing legal case work costs; humanising the issues through telling and sharing people’s stories; supporting whistle-blowers and workers from the detention centres, including teachers, to tell their stories; and mass city protests (including tweeting photos of the ‘poster making train’ on the way to the protests) in Sydney, Melbourne, Perth, Newcastle, Hobart, Brisbane, Adelaide, Ballina, and at the Australian embassies in London and Tokyo.

While the overall policy of offshore detention is still in place, a series of campaigns and actions have mobilised different groups of people around the lived experiences of people working and living in Nauru and Manus, humanising the scale of offshore detention experiences to amplify new narratives with the wider public in Australia.

‘It’s clear your policy has failed’: The hashtag #BringThemHere also intersected with news in early September 2016 of Wilson Security ending their contract with offshore detention centres on Nauru and Manus Island, as documented by Olivia Tseu-Tjoa.

Despite both major political parties adopting hardline immigration policies, this inclusive and popular campaign has been open to all people in Australia to get involved and change the narrative with the wider public across Australia.

6 pastors & 1 nun arrested after refusing to leave Turnbull office until Gov agrees to #BringThemHere #LoveMakesAWay pic.twitter.com/te9y5G2Xt8

— Love Makes A Way (@lovemakesaway) August 29, 2016

Thousands march in Syd today to welcome refugees and #BringThemHere. This is the view from Pitt St mall pic.twitter.com/sRZ7G8ovbL

— Senator Lee Rhiannon (@leerhiannon) August 27, 2016

Australia world leaders in cruelty #EvacuateManus #bringthemhere pic.twitter.com/KYx0W1qAxe

— WACA (@akaWACA) November 9, 2017

#IllRideWithYou

The story: On December 15th, 2014, an Iranian-born cleric living in Australia, entered a cafe in Sydney during the morning rush hour and took the staff and customers hostage. Almost 24 hours later, the siege was over, two hostages were killed and the hostage-taker himself.

Following concern that people wearing Islamic dress would be harassed after the armed man, claiming links to Islamic State, took the hostages, local people used twitter to offer to travel with them spreading a message of solidarity and humanity. One woman started what soon blossomed into a social media campaign to stand in solidarity with the city’s Muslim community.

Tessa Kum, a TV content editor and writer living in Sydney, acted after seeing a tweet that shared Rachel Jacobs’ comments on Facebook in support of a Muslim woman removing her hijab riding the train with her. Seeing this tweet, Tessa Kum offers to accompany anyone in religious attire on her route, using the hashtag #IllRideWithYou. Fellow Twitter users swiftly joined in, offering their support….and actions.

If you reg take the #373 bus b/w Coogee/MartinPl, wear religious attire, & don’t feel safe alone: I’ll ride with you. @ me for schedule.

— Sir Tessa (@sirtessa) December 15, 2014

#illridewithyou reminds me:

— Ken Sekiya (@ki_sekiya) December 15, 2014

Muslim Woman Covers the Yellow Star of Her Jewish Neighbor with Her Veil. (Sarajev, 1941) pic.twitter.com/LTKBsMxk5N

The who: Rachel Jacobs on Facebook, Tessa Kum

The issues: religion, culture, solidarity, multiculturalism, Islam, Islamic State

The medium: Facebook and Twitter

Campaign hashtag: #IllRideWithYou

The time-frame: 24-hours, and the weeks that followed in December 2014

The impact: According to Twitter Australia, there were 40,000 tweets in just two hours using the hashtag #illridewithyou. In four hours 150,000 tweets were posted and 250,000 tweets in less than 24 hours. Social Media ‘clicktivism’ on its own may not be transformative. As an amplifier of voice it helps to build community conversations and many individual actions.

For more: explore the roots of the #IllRideWithYou movement in a news report in The Atlantic, taking place a month after the Operation Sovereign Borders campaign, a program designed to dissuade asylum-seekers and illegal immigrants from entering the country.

#illridewithyou radiates the beauty of Australian mateship. We are many, but together we are one. #sydneysiege pic.twitter.com/cmJonDi7Lc

— Lisa Donaldson APD (@Lise_Simpson) December 15, 2014

Let's not be clicktivists only but #illridewithyou activists....this may well be our finest communitarian hour.

— FatherBob (@FatherBob) December 15, 2014

#stopfundinghate

Today's Daily Mail advertisers include @MarksandSpencer @Gillette @AldiUK @Asda @LidlUK @BootsUK @Nectar @Homebase_UK @SmartenergyGB @Pandora_UK @JourneysEnd2017 @SCSSofas @DFS @BensonsForBeds @Staysure @SandalsResorts @FredOlsenCruise @BiGDUG @CanadianAffair @MercuryHolidays pic.twitter.com/08uQeVGvCd

— Stop Funding Hate (@StopFundingHate) February 10, 2018

The story: The Stop Funding Hate campaign emerged in 2016 when a group of people began to express concern at the way certain newspapers in the UK were using hate and division to drive up their sales. After what it called ‘decades of sustained and unrestrained anti-foreigner abuse, misinformation and distortion’, the UN Commissioner for Human Rights accused some British newspapers (the Daily Mail, Sun and Daily Express) of ‘hate speech’.

The newspapers were making use of relentlessly hostile and routinely inaccurate stories about minorities as a means of driving sales. The problem was seen as part of a rise in hate crime: according to the University of Cambridge and the Economic and Social Research Council ‘Mainstream media reporting about Muslim communities is contributing to an atmosphere of rising hostility towards Muslims in Britain’. Other groups such as refugees, migrants, the LTBTQI community, and people with disabilities were also targeted.

The Stop Funding Hate social media campaign aimed to encourage companies advertising in such newspapers to withdraw their ads, includes actions such as:

- publishing a daily update with detailing who buys ad space in each newspaper, tagging all of the companies involved.

- encouraging individuals to send nice messages to companies, engaging with them directly via public social media channels such as Twitter

- keeping a record of responses from companies and making this publicly available via the campaign website

- producing a series of video adverts to raise broader awareness of the campaign through social media channels

The who: Initiated by Richard Wilson, a former Corporate Fundraiser at Amnesty International and a group of colleagues and friends

The issues: hate speech, hate crime, mainstream newspaper, advertising

The medium: stopfundinghate.org.uk/our-videos – the campaign’s video library

stopfundinghate.org.uk/get-involved/twitter-actions – the campaign’s use of twitter, and Twitter feed @stopfundinghate

The time-frame: The campaign began in 2016 and is ongoing

The impact: By April 2018, less than two years since the volunteer-led and crowd funded campaign began, 34 companies including food retailers, insurance companies, leisure goods outlets and universities, have ceased or committed to continue to avoid advertising in the Daily Mail, Sun or the Daily Express. For a full list of advertisers who have withdrawn their ads, see stopfundinghate.org.uk/about-the-campaign/ethicaladvertisers

We have finished the agreement with The Daily Mail and are not planning any future promotional activity with the newspaper

— LEGO (@LEGO_Group) November 12, 2016

We monitor the environment in which our advertising appears, to ensure the values of a publication are compatible with our own. We have no future plans to advertise within the Daily Mail. 2/2

— Southbank Centre (@southbankcentre) February 16, 2018

*Confirmed* Congratulations to Paperchase, who have promised not to run any further promotional partnerships with the Daily Mail. They have acted promptly in response to customer concerns - this is great news in the run-up to Christmas! #StartSpreadingLove https://t.co/uTKWBdXokC

— Stop Funding Hate (@StopFundingHate) November 20, 2017